Syria earthquake

Situation reports | News | Photo essay | From the field | Video testimonials

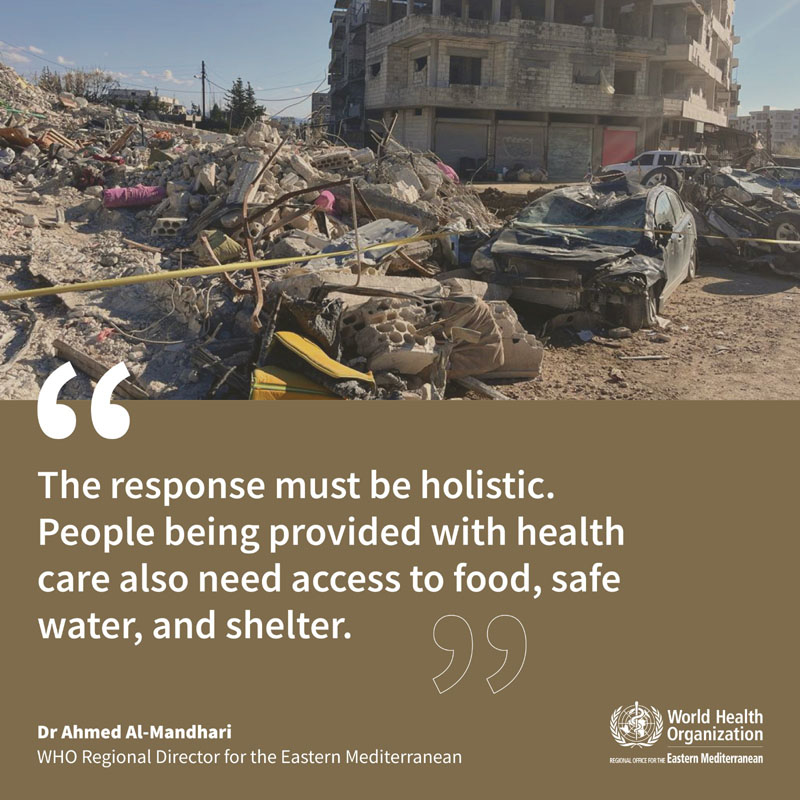

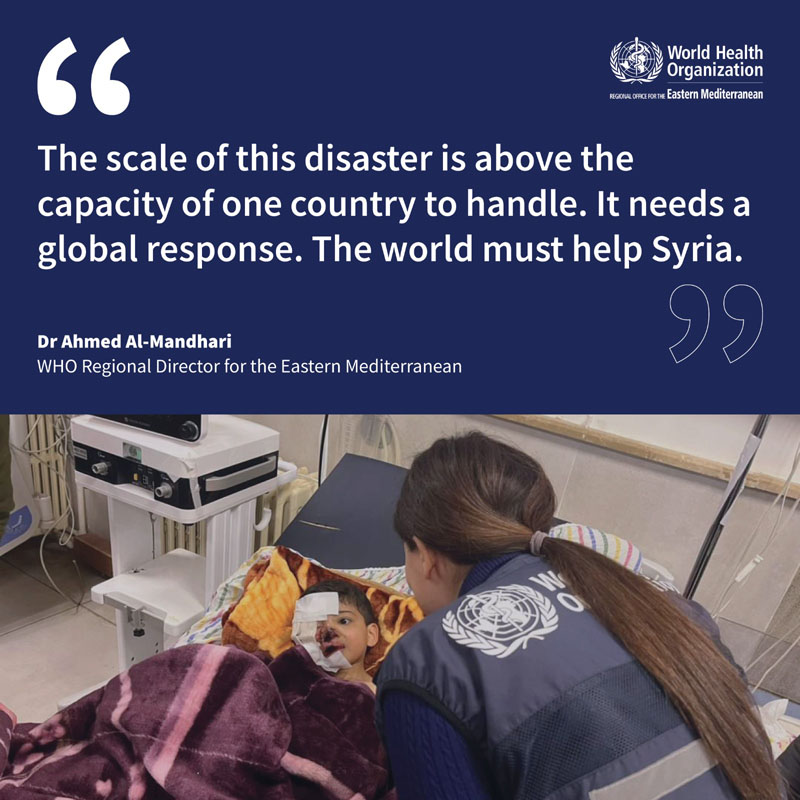

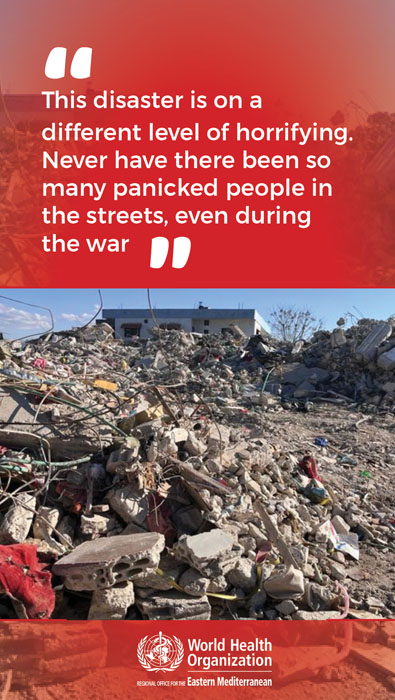

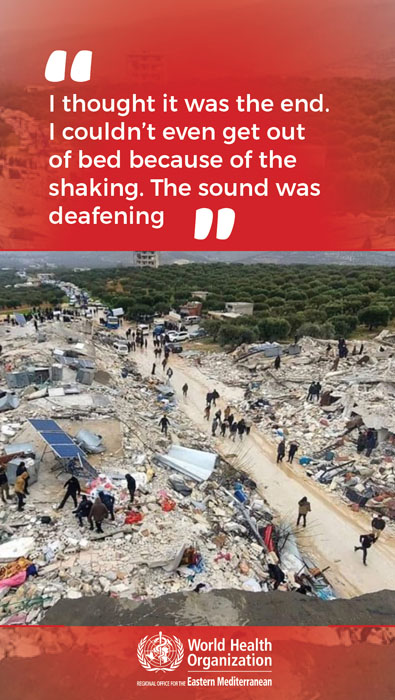

The 7.8 magnitude earthquake that struck southern Türkiye and northern Syria brought horror and devastation to the affected populations on an unimaginable scale. Since the earthquake, WHO has been providing supplies and working with health officials to direct medical teams and support where they are most needed.

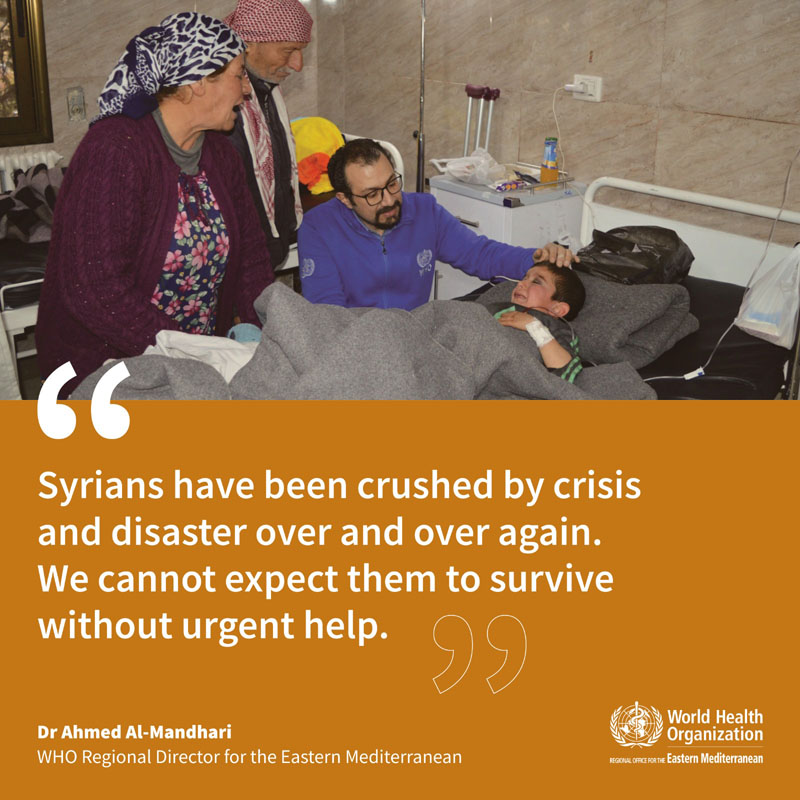

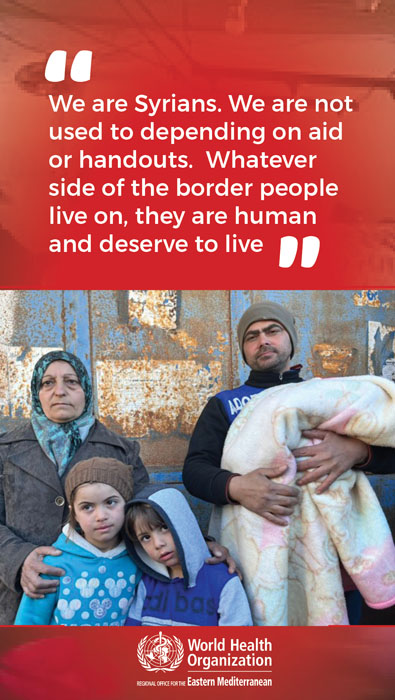

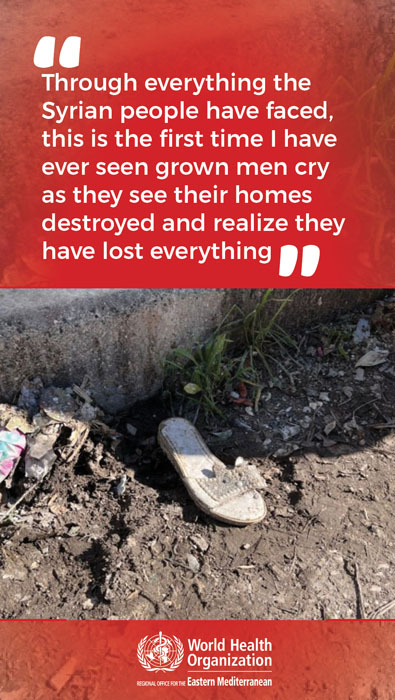

The Syrian people everywhere in the country – who have already lost so much and so many in 12 years of war, major economic decline, and continuous disease outbreaks – once again show the resilience needed to withstand this new, immense, challenge with inspiring determination.

Regional Director's briefing on earthquake in southern Türkiye and northern Syria

Let me again express my deepest condolences to the people of Syria. As my colleague Dr Iman Shankiti noted, we expect the death toll to increase in the coming days. Our hearts and thoughts are with the families and loved ones of those whose lives were lost as a result of this tragic event.

Our priority now is to make sure that those who have been injured receive the life-saving care they need, as soon as possible, to prevent further loss of life and disability. And that those who have lost their homes and livelihoods are not exposed to further public health risks.

Situation reports

Whole of Syria: situation report, 17-30 April 2023

Whole of Syria: situation report, 3-16 April 2023

Whole of Syria: situation report, 20 March - 2 April 2023

Whole of Syria: situation report, 13-19 March 2023

Whole of Syria: situation report, 6-12 March 2023

Whole of Syria: situation report, 27 February–5 March 2023

Whole of Syria: situation report, 20-26 February 2023

Whole of Syria: situation report, 13-19 February 2023

Situation report 12: 4 May 2023

Situation report 11: 20 April 2023

Situation report 10: 2 April 2023

Situation report 9: 30 March 2023

Situation report 8: 23 March 2023

Situation report 7: 16 March 2023

Situation report 5: 15 February 2023

Situation report 4: 13 February 2023

Situation report 3: 10 February 2023

Situation report 2: 9 February 2023

Situation report 1: 8 February 2023

WHO Gaziantep Field Office: situation report 1: 6-12 February 2023

WHO Gaziantep Field Office: situation report 2: 13-16 February 2023

News

WHO and Ministry of Health collaborate to enhance Syria’s medical supply chain

21 March 2023

WHO calls on global community to stand by Syria at Brussels donor conference

20 March 2023

24 hours under the rubble: 10-year-old Fatima lives to tell her story

16 March 2023

WHO and UNICEF launch cholera vaccination campaign in northwest Syria amidst earthquake response

8 March 2023

Novo Nordisk Foundation supports earthquake-affected Syrians with DKK 13 million

6 March 2023

WHO health supplies continue to flow into all areas in Syria affected by the earthquake

23 February 2023

Photo essay

From the field

Quotes from the Regional Director

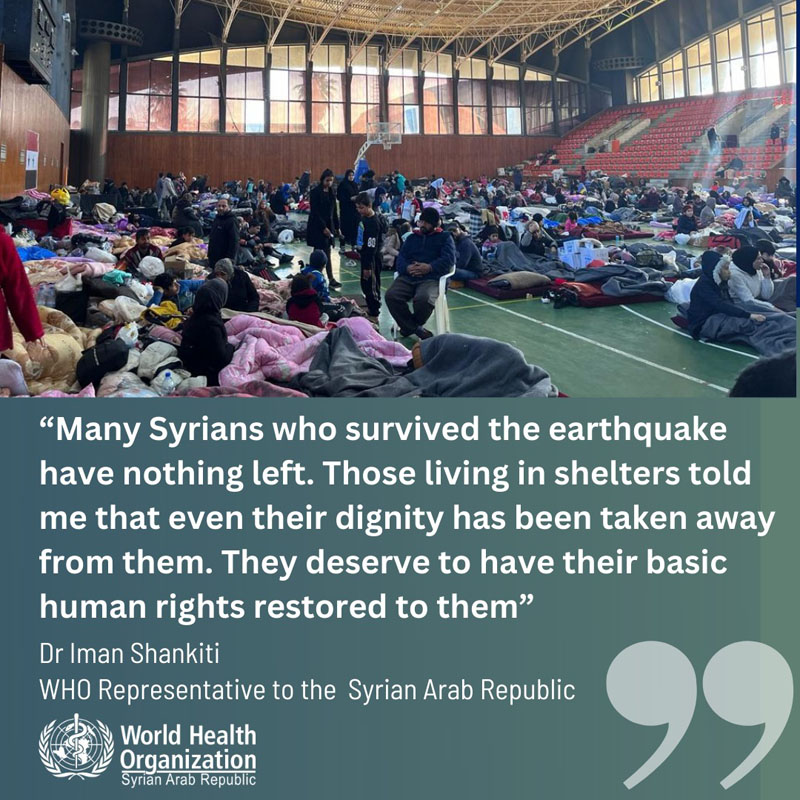

Quotes from the WHO Representative for Syria

Syrians who survived 12 years of war describe the earthquake

Video testimonials

Tuberculosis

In 2018, the rate of TB was 18 per 100 000 people while in 2017, it was 15.8. In 2019, the National TB Programme (NTP) in Damascus reported that 2681 patients had registered for treatment, suggesting a notification rate of 15 for every 100 000 people. The governorates of Damascus, Aleppo and Rural Damascus reported the highest numbers of TB patients (708, 582 and 380, respectively). Based on MoH statistics, Aleppo represents a third of the entire caseload of TB patients in Syria. A survey in Al-Sheikh Maqsood in Aleppo governorate, conducted in July and August 2019, found 300 suspected cases out of 15 000 individuals tested, of which 19 patients were confirmed and treated.

In 2019, 165 NTP staff in Damascus, Homs and Rural Damascus were trained on managing TB patients based on WHO’s global guidelines, conducting laboratory diagnosis and following up on multi-drugresistant TB patients.

Three fully equipped TB mobile clinics have recently been donated to Syria by theMiddle East Response project, which is mobilizing to provide TB services for people in IDP and refugee camps and other closed settings such as prisons. These clinics have been distributed to Aleppo, Deirez-Zor and Rural Damascus governorates. Lengthy international procurement procedures and insufficient funds continue to threaten the future of Syria’s TB centres. A 2018 WHO assessment found that the capacity of laboratories in northwest Syria was weak and human resources were inadequate. There were numerous shortages of TB drugs and the TB case detection rate was low (605 registered cases compared to the 1260 predicted new cases that WHO expects to be detected annually). At the end of 2019, there were three fully functioning TB centres in the northwest, in Afrin, Azaz and Idleb cities, with 59 physicians, laboratory technicians and health staff trained by WHO. In 2019, they diagnosed 314 patients with TB and managed to complete treatment for 114 of them. At the end of 2019, there was still no capacity for active case-finding of tuberculosis patients.

Lengthy international procurement procedures and insufficient funds continue to threaten the future of Syria’s TB centres. A 2018 WHO assessment found that the capacity of laboratories in northwest Syria was weak and human resources were inadequate. There were numerous shortages of TB drugs and the TB case detection rate was low (605 registered cases compared to the 1260 predicted new cases that WHO expects to be detected annually). At the end of 2019, there were three fully functioning TB centres in the northwest, in Afrin, Azaz and Idleb cities, with 59 physicians, laboratory technicians and health staff trained by WHO. In 2019, they diagnosed 314 patients with TB and managed to complete treatment for 114 of them. At the end of 2019, there was still no capacity for active case-finding of tuberculosis patients.

Trauma care

Explosive remnants of war will continue be a threat to individuals, especially children, and strain the health system in Syria for years to come. A national household survey carried out in June 2019 found that over half of all households surveyed had a member who was living with a disability and almost half of households surveyed had two or more members who were living with a disability. The report also found that 27% of people aged 12 and above had a disability. Today’s and future victims will require comprehensive care, including trauma services, mental health support and long-term rehabilitation. To help maintain access to trauma stabilization and emergency surgical care services, WHO donated 21 ambulances to the MoH and the Syrian Arab Red Crescent, and supported five field surgical units in rural Hama governorate that stabilized 4112 patients, including 2547 who required immediate surgical intervention before being referred to nearby hospitals.

In northwest Syria, WHO’s office in Gaziantep delivered specialized trauma and surgical kits and medicines to provide more than 180 000 treatments. In areas accessible from within Syria, WHO supported trauma care for 474 669 patients and delivered 2 354 029 courses of treatment and 108 pieces of medical equipment to health facilities providing trauma care services. A total of 2571 health care workers were trained on trauma care, treatment of patients with disabilities, first aid, prostheses, basic life support, mass casualty events, burns, war wounds and spinal cord injuries. WHO also supported 22 000 physiotherapy sessions and delivered nearly 2300 disability devices.

In the northeast, WHO renewed its agreement with Al-Hekma hospital and signed an agreement with Al Hayat private hospital in Al-Hasakeh governorate to cover the costs of patients admitted for trauma and emergency care. By the end of 2019, the two hospitals had provided 5780 treatments. In October2019, WHO signed an agreement with a third hospital (Al-Teb Al-Hadeeth) in Ar-Raqqa city. A team of physicians from the Bambino Gesù paediatric hospital in Rome re-visited Syria in 2019 to continue training their counterparts in university hospitals inDamascus and Aleppo on the latest techniques inlaparoscopy, interventional radiography, paediatric catheterization, intensive care and cardiovascularsurgery. A total of 24 doctors and 20 nurses from four university hospitals in Damascus and Aleppo were trained. Subsequently, the Syrian physicians visited the Italian hospital and later returned to Syria to train other specialists in their hospitals.

In northwest Syria, WHO’s office in Gaziantep delivered specialized trauma and surgical kits and medicines to provide more than 180 000 treatments. In areas accessible from within Syria, WHO supported trauma care for 474 669 patients and delivered 2 354 029 courses of treatment and 108 pieces of medical equipment to health facilities providing trauma care services. A total of 2571 health care workers were trained on trauma care, treatment of patients with disabilities, first aid, prostheses, basic life support, mass casualty events, burns, war wounds and spinal cord injuries. WHO also supported 22 000 physiotherapy sessions and delivered nearly 2300 disability devices.

Secondary health care

Due to improved access to areas regained by the Syrian government, over half of public hospitals were functioning in 2019, albeit many of them at minimum capacity and with severe shortages of staff, medicines and supplies3. Hospitals in Aleppo, Dar’a, Homs, Idleb, Rural Damascus and northeast Syria were some of the worst affected. WHO delivered more than 230 pieces of medical equipment4 to over 60 hospitals in areas under government control and trained staff in 38 hospitals on neonatal resuscitation. Some 100 hospitals and health facilities in 12 governorates received intravenous fluids, NCD medicines and other supplies. The Organization assessed the status of the national cancer registry in five oncology facilities in Aleppo, As-Sweida, Damascus and Lattakia, and completed a study of the care experiences of cancer patients and their families. It also delivered cancer medicines and diagnostic equipment to the Ministry of Health (MoH) and one NGO and supported 15 287 referrals. The Essential Medicines List was updated in close collaboration with the MoH.

WHO’s office in Damascus supported training for more 2100 health workers from different governorates on topics including the rational use of medicines, pharmacovigilance, patient safety, IPC and supply chain management. A total of 255 female and male civil and biomedical engineers were trained on standard hospital design and rehabilitation, as well as the installation and maintenance of advanced medical equipment. In northwest Syria, WHO trained 210 health professionals on IPC, 40 obstetricians and midwives on neonatal care, 92 technicians on anaesthesia and 35 health care workers on burn management.

Almost three quarters of all health facilities in the northwest have been established since the crisis began in 2011. In late 2019, an assessment of health facilities in Idleb governorate found that, despite poor infrastructure and low capacity, 25 secondary health care facilities (including seven hospitals) were serving a population of 1.6 million, exceeding the minimum humanitarian standards of one hospital per 250 000 people.

Nonetheless, the hospital bed ratio was very low: 3.3 per 10 000 people compared with a pre-conflict rate of 15 per 10 000 people.

Major secondary health care gaps persisted throughout northwest Syria. Hospitals lacked specialized services for patients with cancer and kidney diseases. Trauma patients often occupied the few available beds in intensive care units. In many hospitals, equipment to support orthopaedic and reconstructive surgery was outdated or malfunctioning. Working from Turkey, WHO provided 662 000 treatments for intensive care units, dialysis sessions and chemical attacks and distributed essential medicines, supplies and equipment to seven major referral hospitals. It also supported two projects in 18 general hospitals and 24 intensive care units to improve the quality of care for NCD patients.

Reproductive health

Reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health services are critically important in humanitarian settings, which typically see increases in maternal deaths, unintended pregnancies, sexually transmitted infections, unsafe abortions and GBV. In 2019, most governorates showed considerable progress in providing these services. In 2018, 32 hospitals across the country had neonatal resuscitation programmes; in 2019, this number rose to 38. The number of patients referred to specialized hospitals almost doubled, from 2821 to 5437. There was a similar rise in the number of mothers and newborns benefiting from home care (from 6361 in 2018 to 12 358 in 2019). An estimated 15% of deliveries and 15% of newborns will continue to require life-saving emergency interventions in 2020.

Primary health care

To enhance the coverage of affordable basic PHC services, WHO donated over 2.1 million treatment courses of life-saving medicines (including NCD kits) to health partners and delivered 406 pieces of equipment such as nebulizers, laboratory and ultrasound equipment, pulse oximeters, X-ray machines and generators to ministries, the Syrian Arab Red Crescent and NGOs. The Organization also supported over 5.2 million consultations in PHC centres throughout Syria.

Among the PHC efforts most appreciated by beneficiaries during 2019 was WHO’s donation of 27 mobile clinics to health responders across the country. WHO also provided 12 medical caravans to health partners working in the major IDP camps and informal settlements in the northeast. Each set of two caravans consisted of three clinics and a pharmacy.

Among the mobile medical teams supported by WHO were four teams in Homs and Hama that were providing services for people from Rukban settlement and two teams deployed to schools in eastern Ghouta as part of an oral health project.

WHO integrated NCD treatment services into nine PHC facilities in northwest Syria. More than 23 000 patients were screened for cardiovascular diseases and more than 15 000 NCD consultations were provided. In 2020, WHO intends to replicate the model in other centres in the northwest. WHO also piloted an NCD emergency kit in 12 PHC centres in northwest Syria and trained almost 200 health workers on risk factors for chronic diseases and managing patients with thalassaemia. In line with restoring PHC services, WHO supported centres in Aleppo and Homs with essential medical equipment. During the year, these centres provided health care services to nearly 100 000 people, including physiotherapy for amputees as well as services for patients with artificial limbs and movement disorders. The core package of services at each health centre was reviewed and updated on a quarterly basis. These services covered general clinical services, child health, immunization, nutrition, NCDs, communicable diseases, sexual and reproductive health, mental health and essential trauma care.

In northeast Syria, WHO supported PHC centres and mobile clinics in all three governorates.

Preparedness for chemical events

WHO’s preparedness for chemical events focused on the two regions that saw the greatest number of hostilities in 2019: the northeast and the northwest. A total of 628 health workers in Idleb and Aleppo were trained on responding to chemical events, while approximately 450 clinicians and health workers in the governorates of Aleppo, As-Sweida, Damascus, Hama, Homs, Lattakia and Tartous received advanced bio-chemical training. WHO developed online and print guides in Arabic and Kurdish on the clinical management of chemical events and distributed them to health facilities in the northeast. In the northwest, 18 referral hospitals were provided with 2000 sets of PPE and essential medicines and antidotes.

WHO paid special attention to its staff working in hazardous areas. It stocked staff protection algorithms and chemical escape kits in all WHO offices and vehicles, and pre-positioned 500 sets of PPE, medicines, supplies and antidotes. Medical staff continued as in previous years to be trained on types of commonly used chemical weapons, chemical exposure, trauma care and how to provide a sound public health response to the health consequences of chemical exposure. In addition, WHO senior personnel participated in a training-of-trainers course in Amman on chemical exposure and trauma care.

Polio

Syria has a robust surveillance system for acute flaccid paralysis (AFP). Stool specimens are collected and sent to the WHO-accredited National Polio Laboratory (NPL) in Damascus to determine whether poliovirus infection is the cause of paralysis. Surveillance indicators reached global targets for 2019 with a detection rate of >3/100 000 children under the age of 15. Sewer samples were collected from 16 sites in 13 governorates to exclude the possibility of poliovirus circulating unnoticed within the community. While the Syrian MoH is responsible for training, supervising and managing surveillance staff, WHO provides financial support for transport, incentives for timely collection and analysis, and capacity building.

Massive population displacements in northwest Syria served to emphasize the need to keep AFP surveillance indicators at the highest level. In 2019, 427 cases were detected with a high non-polio-AFP rate. No cases of Sabin type 2 or vaccine-derived wild polio virus were detected. However, the risk of polio remains. Despite limited access to some areas in the northwest, WHO and partners are continuing their monitoring efforts.

In 2019, WHO conducted two nationwide and two subnational polio immunization campaigns in all areas accessible from Damascus. Three polio immunization campaigns for children under the age of five were conducted in all accessible areas of northwest Syria.

National Polio Laboratory in Damascus

The NPL in Damascus carries out viral isolation and intra-typic differentiation of the poliovirus. Laboratory staff have been trained on genetic sequencing, which will enable the laboratory to perform this function once it receives the necessary equipment. In 2019, the NPL successfully passed the annual accreditation exercise carried out by WHO. Accreditation provides formal confirmation that the laboratory has the capability and the capacity to detect, identify and promptly report wild and vaccine-derived polioviruses that may be present in clinical and environmental specimens. WHO funded all supplies and equipment required by the NPL and supported capacity-building for senior NPL staff through internal and external workshops, in coordination with the WHO Regional Office in Cairo.

Nutrition

The 2019 SMART survey revealed several pockets of emerging chronic and acute malnutrition. The survey confirmed that infant and young child feeding practices remained poor, with only 28.5% of mothers choosing early initiation of breast feeding. Similarly, only 18% of mothers exclusively breastfed their infants during the first six months of life. To date, 38 hospitals have been trained on the baby-friendly hospital initiative to increase the initiation of breastfeeding within the first hour of birth.

At the end of the year, the nutrition surveillance system consisted of a network of 827 health centres serving 980 000 beneficiaries. A total of 707 health facilities offered infant and young child feeding counselling, up from 592 in 2018. Three new stabilization centres for the treatment of SAM with medical complications were established in Aleppo, Al-Hasakeh and Ar-Raqqa, bringing the total number of centres supported by WHO to 25. In 2019, these centres treated 2145 children under the age of five, compared with 905 in 2018. The highest number of admissions was in Al-Hasakeh governorate (more than 650), reflecting the dire health status of children in Al-Hol camp who escaped ISIL’s last stronghold in early 2019. WHO is working with other UN agencies including UNICEF and WFP, both of which are supporting therapeutic and supplementary feeding programmes.

A total of 19 440 cases of global acute malnutrition (GAM) were detected and referred for treatment in 2019 (GAM means both severe acute and moderate acute malnutrition). The number of cases fluctuated only slightly compared with previous years. The 25 stabilization centres distributed across the country covered most needs but required regular support for nutrition therapeutic supplies, equipment and training of staff. Stabilization centres are still needed in Ar-Raqqa and Idleb.

Mental health

WHO and its partners have decentralized mental health care and increased community-based approaches. For example, trained and supervised doctors and health workers are providing integrated mental health care in over 540 PHC centres across the country. Two psychiatric wards in Lattakia and Damascus provide management for mental, neurological and substance use disorders. In the northeast, through close coordination with health partners, WHO continued to transport patients in acute need of special care to Aleppo mental health hospital.

In 2019, health partners across the country were provided with 121 202 treatment courses of psychotropic medicines, and 552 316 MHPSS services were delivered, often through local NGOs and innovative community-based methods. WHO trained Reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health services are critically important in humanitarian settings, which typically see increases in maternal deaths, unintended pregnancies, sexually transmitted infections, unsafe abortions and GBV. In 2019, most governorates showed considerable progress in providing these services. In 2018, 32 hospitals across the country had neonatal resuscitation programmes; psychosocial workers throughout Syria (including the northwest) on Problem Management Plus, a low-intensity psychological intervention that tackles depression, anxiety, problem-solving skills and resilience for adults.

WHO’s office in Damascus supported training for 725 physicians on mhGAP. Hundreds of health care workers were trained on basic, family and group counselling, psychological first aid and first-line support for GBV survivors. The learn–work–learn method applied helped to ensure that learning was translated into practice and reinforced at further training sessions. Additionally, 26 journalists were trained on communications around suicide prevention and MHPSS.

In northwest Syria, WHO supported 45 health facilities with regular supplies of mental health medicines and covered the operational costs of the acute inpatient unit in Sarmada mental health centre, as well as four mental health mobile clinics and a 24-hour telephone helpline. With the support of the Turkey Humanitarian Fund and the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, in 2019, this number rose to 38. The number of patients referred to specialized hospitals almost doubled, from 2821 to 5437. There was a similar rise in the number of mothers and newborns benefiting from home care (from 6361 in 2018 to 12 358 in 2019). An estimated 15% of deliveries and 15% of newborns will continue to require life-saving emergency interventions in 2020.

MHPSS services were integrated into 42 PHC centres, 32 mobile clinics, 20 hospitals and eight specialized centres. Overall, approximately 280 psychosocial workers now work in 118 facilities in northwest Syria that provide MHPSS services. WHO trained 945 humanitarian and community health workers on psychological first aid, enabling them to provide immediate support to the newly displaced and refer them for MHPSS. In addition, 28 mh-GAP-trained doctors in Afrin underwent six months of training, field supervision and coaching.

Late in 2019, WHO took over six non-specialized MHPSS services in northern Syria from an international NGO whose future was threatened by insufficient funds. Today, all six facilities are continuing to provide quality MHPSS services.

The school mental health programme, which was launched in 2018, continued in 2019. Teachers, counsellors and social and community workers in schools and community centres were trained on how to detect, help and refer children suffering from mental health disorders. WHO also developed a mental health preparedness plan for interventions in emergencies in the northeast and the northwest.

Humanitarian agencies are increasingly concerned about the potentially damaging effects of stress on services and staff performance. In northwest Syria, WHO provided stress management through a training-of-trainers programme and training on selfcare, peer support and coaching for 328 aid workers.

The outcome of WHO’s capacity building was reflected in the improved effectiveness and performance of Syrian health and community care providers, clearly documented in MHPSS care outcomes for IDPs, returnees and host communities.

WHO strengthened advocacy and coordination efforts by chairing an MHPSS technical working group with partners and stakeholders within Syria. Work with the ministries of health and education, other UN agencies and national and international organizations led to several agreements and work plans to enhance universal coverage for mental health and combat stigma and discrimination.

WHO’s efforts to gradually integrate mental health into the health care system in Syria have demonstrated the feasibility of not only delivering, but also expanding, mental health services in the midst of a protracted crisis while simultaneously aiming to reduce stigma and discrimination against people with mental health problems.